'It's like a miracle': Blind woman can see again after Vancouver surgery

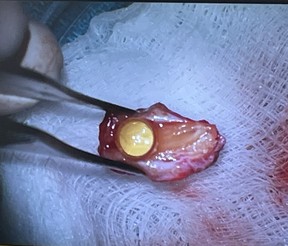

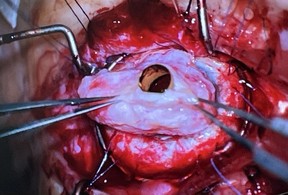

A lens was put in Gail Lane's tooth and inserted into her eye, restoring her vision. She was the first patient in Canada to have the remarkable surgery

Article content

She was blind for a decade, but Gail Lane’s sight is slowly returning after she made history as the first Canadian to have her own tooth, with a lens drilled into it, inserted into her eye.

“It’s like a miracle,” Lane said of the strange sounding operation that is new to Canada but was pioneered in Italy more than five decades ago.

Lane’s vision has returned gradually after the two-step procedure was completed during surgeries in February and May.

Early on, she could see light, and then colours. Objects such as cars and furniture came into focus about a month ago. The first substantial thing the Victoria resident could identify was the wagging tail of her partner Phil’s black lab, Piper.

“I could see Piper’s tail moving. I couldn’t see his whole body, but I could see his tail,” she recalled Thursday. “I can now start to actually see his features. He’s got some little white whiskers growing under his chin. And now I can see his eyes.”

It’s a dream come true for Lane, who had full sight until age 64, when she had a rare reaction to prescription drugs that led to scarring on her eyes and the loss of her vision.

Restoring that sight, a decade later, has been a long, sometimes scary journey, but one for which she is grateful.

“Two operations later, my recovery is going well and I’ve got some sight returning. Life is different now,” she said. “I can now go outside and see the beautiful blue sky and the leaves on the trees.”

The doctor who brought osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis, nicknamed tooth-in-eye surgery, to Canada is Providence Health ophthalmologist Dr. Greg Moloney, who performed this procedure on seven patients in his home country of Australia before relocating to Vancouver in 2021.

Lane was the first of three Canadian patients he operated on at East Vancouver’s Mount Saint Joseph Hospital earlier this year. All are now in different stages of recovery with sight returning in varied ways and at at different speeds, he said.

“We’re seeing all three patients get their vision back,” he said. “It’s usual to have some ups and downs in the early course after the surgery is done. And that’s happening, but nothing really that’s major.”

In February, Moloney and members of his large operating team extracted canine teeth, coincidentally also known as eye teeth, from the three patients. The teeth were shaped, holes were drilled in the middle and plastic lenses were glued inside.

The teeth were sewn into the patients’ cheeks to allow a layer of tissue to form around them before being removed three months later.

In a followup surgery in May, Moloney replaced Lane’s damaged iris with the tooth, and used its newly formed tissue to sew it to her eyeball. The plastic lens acts like a telescope, allowing light to come in and hit the back of the eye, which still functions.

Of the three patients, Lane had the longest wait to get her vision back, largely due to bleeding inside the eye that took some time to clear, Moloney said.

“We were always very frank with her that she was our oldest patient. We weren’t sure how healthy the back of her eye really was going to be,” he said.

Two weeks ago, though, while wearing prescription glasses, Lane achieved 20/50 vision — she could see something 20 feet (six metres) away that a person with normal vision could see at 50 feet (15 metres).

That was “way beyond” what his team had expected for Lane. “For all of us to see the change, it’s hard not to feel emotional about it,” Moloney said.

The second patient was Brent Chapman, 34, from North Vancouver. He lost his vision as a teenager after having a severe reaction to a painkiller, which triggered the same rare condition that Lane developed, Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

About two weeks after his second surgery in May, Chapman had impressive 20/30 vision while wearing glasses. The young man was euphoric.

“It’s been such a journey. This has really dominated their lives,” the doctor said of Chapman’s family. “He hasn’t gotten to have a normal childhood or even adulthood so far. And I think we are really close to giving that back to him.”

Because Chapman had undergone about three dozen previous surgeries, all in an effort to restore his vision, the back of his eye was not as structurally strong compared to the other patients. As a result, his tooth tilted a bit during the healing process, which weakened his vision.

So Moloney performed a followup procedure this week to straighten and reinforce the tooth, which he anticipates will return Chapman’s sight to how it was in the spring.

The third patient, a 29-year-old man from outside the province whose name hasn’t been released, had the fastest recovery; he was able to read within a week of his May operation. Around the same time, Moloney witnessed him pour water into a glass, filling it precisely to the top.

“His auntie burst into tears,” Moloney said. “The tiny, basic functions of life that we all take for granted, some of these patients haven’t been able to do for, in his case, 17 years.”

That man now can take public transportation and visit the pharmacy on his own.

“He really has just turned back into a normal, functional patient,” Moloney said. “It’s incredible.”

Even though Lane’s vision is not strong enough yet for her to read or walk independently, she has had equally incredible moments. People are starting to come into focus, including her partner Phil, whom she met while blind so is seeing for the first time; her friends’ faces, which had been frozen in time in her memories; and Moloney, the man responsible for making it all possible.

“I just put my hands on his cheeks and said, ‘I can see your handsome face,’” Lane recalled.

As her recovery continues, she has more goals she would like to achieve — seeing her clothes clearly enough to pick out what matches, playing mah-jong with her friends, or starting to golf again.

“My vision isn’t perfect, but it’s certainly much better than being blind. And I’m looking forward to further changes and discoveries,” she said.

“Being able to be more mobile, perhaps on my own, where I’m not having to use a cane. But these are all works in progress.”

Since Postmedia first reported in February on this historic surgery, Moloney’s office has been flooded with requests for help from across Canada and the U.S., where no doctors do this complicated procedure. However, only a tiny percentage of blind patients are good candidates for this type of surgery — typically they have had scarring on their eyes due to some type of trauma.

Three people, from Calgary, Ontario and Newfoundland, have been chosen to be Moloney’s next patients. They are expected to undergo the surgery this fall.

The financial backing for Moloney’s first surgeries came from $430,000 in philanthropic donations to the St. Paul’s Hospital Foundation.

The surgeon argues Health Canada should provide funding for any future operations, since he is the only doctor in the country doing this work and some patients hail from outside B.C.

“In countries where this has been robust and long-running — and I’m speaking really about the U.K. and Singapore and Italy — there has been federal money given to support the program,” Moloney said. “I do hope that the results that we’ve created here will help people understand that it is important.”

In the meantime, Providence has pledged to put permanent funding for Moloney’s clinic into its annual budget, a spokeswoman said.

This article was originally published in the Vancouver Sun on August 1, 2025.

-

Living with age-related macular degeneration (AMD): Learning to 'concentrate on what I can do and what I can see'

Living with age-related macular degeneration (AMD): Learning to 'concentrate on what I can do and what I can see' -

How I care for vision loss: A mother and son's journey beyond limitations

How I care for vision loss: A mother and son's journey beyond limitations -

How to protect your eyes from the hidden dangers of UV exposure

How to protect your eyes from the hidden dangers of UV exposure -

EyesOnGenes campaign: How genetic testing can improve diagnosis and treatment of inherited retinal diseases

EyesOnGenes campaign: How genetic testing can improve diagnosis and treatment of inherited retinal diseases