How curling in Canada evolved from recreational origins to become a competitive sports juggernaut

Once upon a time, a day at the rink would be just an excuse to hang out with some buddies. Not anymore

Article content

The sport of curling has rocked our nation for more than two centuries. Generations of Canadians have embraced the game, which has evolved over the decades.

Its pinnacle competitions declaring national champions — the Brier and the Scotties — date to 1927 and 1960 respectively, and now run alongside Olympic trials, Grand Slams and other international events featuring elite athletes from around the world. Curling is now regularly televised, with players wearing microphones so fans can hear the emotion on the ice and the game strategies. Indeed, it is the most-televised women’s sport.

And despite the sport’s growth around the world, Canada reigns as the top curling nation.

This year’s Scotties — the women’s championship — runs from Feb. 14 to 23 in Thunder Bay, Ont., and the Montana’s Brier — the men’s championship — from Feb. 28 to March 9 in Kelowna, B.C.

So how did we get from the game’s recreational beginnings to a highly competitive sport? Through many, many changes. To help explain the evolution of curling, we’ve enlisted the help of curling gurus — Olympic medallists-turned-broadcasters Cheryl Bernard and Kevin Martin, and five-time Olympic coach Paul Webster — to guide us through the eras.

Smoke ’em if ya got ’em! The social era

The years: From well before our time through 1970

The rock stars: Everybody at the rinks

Tales of early days at the community curling rink often revolved around the social aspect of the game.

It was the night out that Canadians needed to survive during the deep-freeze days of winter.

“It was about getting out in the community and having a social opportunity,” Bernard said. “You’re balancing curling with full-time jobs, and there was no money in it whatsoever. It was just a social event.

“And probably a lot of it, you were playing on natural ice.”

There were certainly a lot of people playing the game.

Calgary itself boasted the Big Four Building, billed as the largest curling rink in the world.

“I remember the Big Four — 48 sheets of ice,” Bernard said. “Oh, yeah … the Big Four in its heyday had 24 sheets downstairs and 24 sheets upstairs. You wouldn’t have believed how crazy it was.

“And, of course, ashtrays everywhere.”

Indeed, smoking was commonplace, as were frosty beverages to help wash down all the fun.

Even on the ice.

“That was one of the big deals — you had benches halfway down the sheet, and they had ashtrays,” Martin said. “Everybody was smoking out on the ice, even the top athletes. Of course, that hasn’t been a thing for a long, long time.”

It’s true that with today’s commitment to fitness, sucking back a Labatt Blue or puffing on a Du Maurier comes accompanied by second thoughts.

But it was prominent back then, with cigarette sales even helping to put curling on the map.

In fact, it was George J. Cameron — the president of a subsidiary of the Macdonald Tobacco Company — who brainstormed the concept of a Canadian championship way back in 1924.

The first Brier — the Macdonald Brier — was won in 1927 by Nova Scotia’s Murray Macneill. It was the Macdonald Brier all the way through to 1979, after which Labatt picked up primary sponsorship through to 2000.

“Curlers sometimes were spent because of the parties that were going on,” Webster said. “You talk about the train that would pick everyone up across Canada and take them to the Brier. By the time, they got to the Brier, they were spent. When Labatt was sponsoring it, there was unlimited beer.

“So part of the reality of that activity was out-lasting your opponents off the ice sometimes.”

From 1972-79, the women’s national finale was branded the Macdonald Lassies Championship, sponsored by Montreal’s Macdonald Tobacco Co.

“You had somebody like (1967 Brier champ) Alfie Phillips coming out of the hack with a cigarette or a cigar in his mouth — whatever he had — throwing a shot,” added Webster. “It was just the way it was then.

“But the curling wasn’t about smoking. The essence of it was being able to put a team together with your buddies. If you talk to a lot of curlers in their 60s, 70s and 80s, they yearn for the years of the past where it was your pure club team.

“And if you had a talented skip, you’d win some games.”

They’ve got talent! The competitive era

The years: 1960-75

The rock stars: Matt Baldwin, The Richardsons, Joyce McKee, Vera Pezer

There were certainly a few talented skips that turned winning into an annual affair.

“Matt Baldwin,” said Martin, recalling the 1954, ’57 and ’58 Brier winner from Alberta. “If you talk talent, that’s a guy who had talent.

“He was one of the first guys to slide down the sheet. And that changed the game at that time, because there was no rule to have to let go of the rock by the hog line. That wasn’t a thing yet.

“Of course, it didn’t take long to change that, because a guy like Matt could slide halfway down the sheet.”

In the years immediately after Baldwin’s run, it was Saskatchewan’s Richardsons — Ernie, Arnold, Garnet and Wes — with four wins in the next five Briers through 1963, followed by multi-year kings in Alberta’s Ron Northcott (1966, ’68 and ’69) and Manitoba’s Don Duguid (1970, ’71).

“True gentlemen,” Martin says of the Richardsons. “They kind of changed the game with wicked talent.”

On the women’s side, McKee won the first two national women’s titles in 1960 and ’61.

The six-time Canadian queen from Saskatchewan sure had the talent and the attention of fellow females in the game.

“Joyce McKee is probably the person that, in my opinion, moved curling forward from being just a social community sport to a competitive sport,” Bernard said. “She’s the one who I can remember that really impacted me.”

British Columbia’s Ina Hansen, too. She won in 1962 and ’64.

Then came Alberta’s Gail Lee and Hazel Jamison in 1966 and ’68, before a return to more McKee, who joined Vera Pezer to co-captain their Saskatchewan squad to wins in 1969, ’71, ’72 and ’73.

“Vera Pezer was about the mental side of the game, too,” Bernard said. “She went down that path early.

“It was a transition from it being a fun community thing into it having potential to be something competitive that maybe people want to watch.”

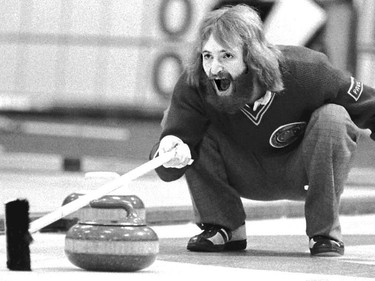

Children of the corn no more: the push broom era

The years: 1975-present

The rock stars: Paul Gowsell, Less Rowland, Eddie Lukowich

The transition was happening in curling technology, as well, with the corn broom being brushed aside for the push broom.

While Calgary’s Bruce Stewart introduced it in the 1960s, the push broom didn’t gain traction until 1975.

Two Calgary Winter Club rinks — skipped by Gowsell and Rowland — used them to win national championships in March, at respective Canadian juniors and Canadian mixed events. They ushered in a new era.

Lukowich’s entire lineup sported push brooms for the 1978 Brier triumph.

The last corn broom team to win the Brier was Saskatchewan’s Rick Folk in 1980.

“Although corn brooms were brought in to make the rock travel further, you could also drop corn on the ice to slow down rocks if they were going too fast,” Bernard said. “You could kind of just swish your broom and corn would drop on the ice, and the rock would slow down.

“I wouldn’t call it cheating — people were just looking for an edge.”

But it’s been push brooms since, although Broomgate — back in 2015 — and Broomgate 2.0 — now in mid-push — have brought controversy to the sport with their new and super improved foam heads.

The Crazy ’80s: The strategy era

The years: 1980-89 and beyond

The rock stars: Colleen Jones, Connie Laliberte, Heather Houston, Pat Ryan, Ed Werenich

There was nothing corny about curling in the 1980s.

Instead, the game was taking off.

That’s when the Scott Paper Company rolled in to sponsor the women’s national championship. The Scott — eventually becoming the Scotties — Tournament of Hearts took on household fame.

“The Scotties sort of legitimized curling beyond just being a community thing in the curling club,” Bernard said. “It moved out of the rural towns and playdowns started to get organized, so that women could compete in the Canadian championships.”

And the women who won those championships became household names.

Jones, from Nova Scotia, won her first of six Scott titles in the paper company’s initial sponsorship year of 1982.

Laliberte, from Manitoba, was the queen three times between 1984 and 1995.

Houston’s Ontario team won back-to-back titles in 1988 and ’89.

“That’s when strategy started to be considered,” Bernard said. “People started to analyze rock placement and reading the ice, so it wasn’t about just going out there. And we were tracking what was successful in a game, whereas that was never done before.”

Strategy was also on the uptick among the men.

While Alberta’s Ryan was a huge hitter, Ontario’s Werenich had more of a soft touch. But both took home two Briers — Werenich in 1983 and 1990, and Ryan back to back in 1988 and ’89.

“I loved Eddie because he wanted rocks in play,” said Webster, who hails from Southern Ontario. “He was a guy who could make a peel with board weight. So he was still the everyman’s curler, because he had that ability to just make little hits and rolls. He definitely was the guy who wanted to make the finesse game.

“I think if he was playing in his 40s today, he’d be doing extremely well with the five-rock and no-tick rules. They would be right up his alley.”

Plenty of famed men earned Brier wins in the ’80s and on into the ’90s, including Folk (’80 and ’94), Manitoba’s Kerry Burtnyk (’81 and ’95), Northern Ontario’s Al “The Iceman’ Hackner (’82 and ’85) and Ontario’s Russ Howard (’87 and ’93).

“It was just a lucky time,” said Martin, who followed with national championships in 1991 and ’97. “You had so many provinces that had such good players.”

Manitoba’s Jeff Stoughton strong-armed his way to Brier triumphs in 1996 and ’99 before Alberta’s Randy Ferbey and The Ferbey Four made a remarkable run of four titles in five years — in 2001, ’02, ’03 and ’05.

“There was no real one way to play the game anymore,” added Bernard. “People weren’t just hitting up and down the ice, because that became an issue and the three-rock rule came into play. But I think that players started to look at the game differently and adapt strategy.”

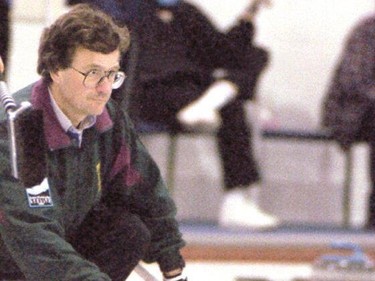

Honing their craft: The practice era

The years: 1980s-present

The rock stars: Ed Lukowich, Kevin Martin

With strategy came the fundamental need for practice, something that didn’t fit the bill back in the early days of curling.

No time for that with games to be played.

Besides, who wanted to spoil the good times with practice?

“It’s true — nobody really practised,” Martin said. “To get good, you would just play a ton of games.

“I remember (1974 Brier champ) Hec Gervais telling me he would play in more than one bonspiel event in the same weekend. So he would zoom back and forth from one to the other and back to the other, and if he lost out in one, he could still win the other. Nobody would even think of doing that now.

“One year, he told me, he played over 300 curling games in a year. That’s the way it was in that era.”

Martin himself remembers his idol, Lukowich, helping to change the opinion of practice.

The two-time Brier king — in 1978 and ’86 — was one of the early pioneers of perfecting his craft by using ice time outside the actual games.

“Lukowich was like that — he practised a ton,” Martin said. “It helped him to get full control over the way he threw the rock with a flat-foot slide. He could throw hits like crazy — over 100 miles an hour.”

But nobody perfected practice like Martin himself eventually did, spending five or six hours daily on the ice at the Edmonton clubs where he worked.

“And that practice went hand-and-hand with the ice getting better, so you could make more shots,” added Bernard. “So then players chose to practice more and search for greater precision.”

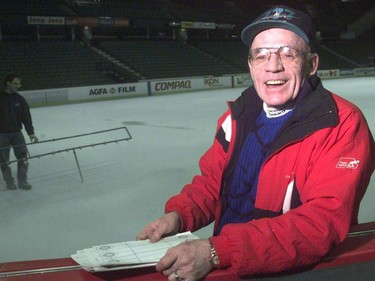

Time and space: The Shorty Jenkins era

The years: 1974-2013

The rock stars: Shorty Jenkins

Better ice was thanks in big part to Clarence W. ‘Shorty’ Jenkins.

Call him what you want — the ‘Zen Master of Ice’ or the ‘King of Swing’ — Shorty became an ice technician extraordinaire shortly after competing in the 1974 provincial championships and noting the terrible condition of the ice.

But Jenkins didn’t stop at trying to perfect pebbled ice.

It was Shorty’s brainstorm to time the rocks, and soon stopwatches became key to a night at the rink.

Indeed, his pursuit of ice perfection and his study of time and space helped improve the game.

“Then Shorty started to sandpaper the stones, and that really changed the game of curling,” Martin says of Jenkins, who was known for his pink-coloured accessories — leather pants and cowboy hat and boots. “Because in order to get curl on arena ice, you really needed to sandpaper the rocks. And once you get curl in the ice, then strategy is important, because then a lot of shots are makable.

“The Skins games was where the curl really started to come into the game, because Shorty was papering the rocks.”

Ice, ice, baby! The better ice era

The years: The 1980s-present

The rock stars: Those with a head for strategy

Yes … an ever-improving playing surface certainly helped change the game.

And it went hand in hand with the uptick in strategy.

“Big change in strategy in the ’80s,” Martin said. “It kind of went with ice conditions, because the ice was very very straight before that.”

Webster says it really wasn’t curling before that.

After all, the term ‘curling’ itself inspires the idea that there is some sort of curl to the game.

“With the rules and ice conditions the way they were, it was truly ‘bowling’ on ice,” Webster said. “You’d wait for a miss on one of the peels, and then you’d hope you’d find that draw weight. And if you ever scored two in a game, nine times out of 10, you were winning it. Those games were just radically different from what you’d see today.”

Need proof?

Check out the throwback games on Curling Canada’s YouTube channel.

Martin himself has VHS footage at home of a match against Werenich in the 1997 Flexi-Coil Curling Classic in Saskatoon.

“It’s funny,” Martin said. “We were taking ice just outside the edge of the four-foot (circle) to draw to the button. There was like two feet of curl — that’s it. That’s how straight the ice was.

“I remembered that ice being swingy and keen and just great. But two feet was a lot of curl back then. And we thought it was fast — it was 13½ seconds (from hog-line to hog-line).”

That kind of curl and speed would never be accepted these days, especially at the big events.

“There was never a year that you were going, ‘Oh, my gosh, the ice is amazing,’ ” Bernard said. “But I would say in the early ’90s is when you were starting to get some good arena ice. Now, that being said, I remember going to a Canadians in ’92 (in Halifax) and the sheets were melted for the first game, so they had an issue.

“You know … there’s always those little things. But the early ’90s was when ice-making technology allowed for better ice, which then allowed for more aggressive gameplay.”

‘Howard Rule’ or ‘Moncton Rule’? The three-rock era

The years: 1993-2002

The rock stars: The Howards, Sandra Schmirler

With better precision and games generating little offence came the need for the free-guard zone.

It was the Howards — Russ and younger brother Glenn — who tinkered with the idea of allowing for lead rocks to stay in play longer. And they brought it forward — with overwhelming acceptance — during an event in Moncton.

Their version of the free-guard zone was the four-rock one, which was modified and adopted by the World Curling Federation ahead of the 1991-92 season.

Canada’s curling body kept it as a three-rock rule before moving to four in 2002.

“The strategy changed with those rule changes,” Webster said. “Now you’re playing a chess match, because I’ve got some stones that you have to deal with. You can have nine or 10 rocks in play now — and that’s entertaining.

“Before the three-rock rule, strategy meant nothing. If you threw up a centre guard, I just got rid of it if I thought you were better than me. If you put up a centre guard and you knew I was better than you, then it was a mistake, because I would just go around it and try to get two. And if I got that two and I was better than you, then the game was over — and sometimes we still had nine ends to play.

“So we were honestly waiting for the miss.”

Manitoba’s Vic Peters won the first Brier with the three-rock rule in place, and the Howards the next in 1993.

Cue Saskatchewan’s Sandra Peterson on the women’s side with the 1993 Scotties victory and again in ’94. She’d win again as Sandra Schmirler in ’97 and be considered one of the finest strategists ever in the sport.

“She was a very smart skip,” Bernard said. “Sandra was precision and strategy.

“I loved Sandra Schmirler,” added current skip Kerri Einarson. “I loved her demeanour on the ice and how she was. She had the fieriness, and I loved that. I was so young when she won, but I think she helped change curling.

“It was super sad when we lost her (in 2000). She would’ve done so much more.”

We are the world! The WCT era

The years: 1992-present

The rock stars: Eddie Lukowich, John Kawaja

With the game growing, it was time to bring curlers separated by miles of Canadian road and oceans together more often.

Lukowich was the guy to do just that — with help from two-time Brier and two-time world champ John Kawaja, among others — by launching the World Curling Tour in 1992.

The WCT was comprised of men’s-only events — a whopping 48 — in the first year, and the circuit welcomed women a few years later.

“That was a big difference, because before that, the Brier and the Scotties were kind of it,” Martin said.

In 1995, the $70,000 Telus West Edmonton Mall Curling Classic sprang to life, with Martin, Peters, Burtnyk, Folk, Gowsell, Russ Howard, Winnipeg’s Jeff Stoughton and Regina’s Randy Woytowich all starring.

The $150,000 FlexiCoil Curling Classic in Saskatoon was also in the WCT mix.

“The WCT provided us the ability to play on elite teams on a regular basis as opposed to just going back to the club and mixing it up with club curlers,” said Bernard, an original WCT committee member. “It was about really trying to challenge ourselves. And it was about building the profile of the game — we worked to get it on TV more.

“And instead of just playing in your province, we’d now start travelling across the nation — and that was unheard of before that. And there’s money to be won — you’re not making a living of it, but you’re covering some of your costs.”

Indeed, suddenly there was financial incentive — not just in purse prizes, but in sponsorship deals.

Grand ol’ game grows even more: The slams era

The years: 1993-present

The rock stars: Kevin Martin, Kevin Albrecht

Even more opportunity came from elite spiels that popped up alongside the WCT events.

In 1993, The Players’ Championship was born — originally the $120,000 VO Cup, won by Russ Howard in Calgary — which was “kind of the initial start of the Grand Slam,” Martin said.

It nearly died a few years later, but TSN stepped in with a TV deal to keep it going. It eventually led to bigger thinking.

“In 1998, I had this idea of having a Grand Slam like tennis and golf,” Martin said. “And just by chance, I went to Toronto to speak, and Kevin Albrecht — a marketing fellow out of IMG, president for Canada — sat down with me and had a coffee, and we started BSing about curling. And that’s how the Grand Slam started.

“He got the sponsorship and the TV deal, but we had to have 18 of 20 top teams in Canada sign contracts to not play in the Brier playdowns. We gave the players big-money events beyond the Brier, which is amateur. And the season would go from October all the way through April. That started in 2001.

“The players walked away from playing in the playdowns, which means they couldn’t go to the world championships for all those years,” continued Martin. “We had boycotted the playdowns to get the Grand Slam started.

“And here we are all these years later, and the Grand Slams are doing fantastic.”

They are world-wide events, linking the globe’s curling nations together beyond the world championships.

“It changed things internationally,” Martin said. “It gave a lot of teams who were not quite good enough yet — like Peja Lindholm — a chance to improve, and then it wasn’t long after that Peja beat us five times in a row.

“Because of the grand-slams, they were able to really play a lot internationally.”

And they were all playing for bigger purses — $175,000 at the 2024 Players’ Championship — which helped to cover the costs of such vast travel to the Slams.

Of course, those grand events all furthered the growth of the sport globally.

“At the Masters (in January), we had three Japanese teams and three Korean teams on the women’s side,” added Martin. “That would’ve been unheard of 20 years ago … impossible. But the game is so world-wide now. And a lot of that has to do with the Grand Slams and the Olympic Games.”

Keeping up with the Joneses — and the Kell(e)ys: The aughts era

The years: 1999-2010

The rock stars: Colleen Jones, Jennifer Jones, Kelley Law, Kelly Scott

While the women didn’t get in on The Players’ Championship until 2006, they were still making noise in the curling world.

Big noise, with massive personalities and stars.

“The only person I saw that actually was able to work around the four-rock rule was Colleen Jones,” Bernard said.

“She just had that kind of inner grip that she could play and be comfortable in a tight game and lead by one point through the whole game and make a shot at the end.

“The other thing that I will say Colleen Jones showed the world was team chemistry.”

Jones racked up Scott titles in 1999, 2001, ’02, ’03 and ’04, marking an incredible run marred only by B.C.’s Kelley Law in 2000.

Then it was Manitoba’s Jennifer Jones — in 2005, ’08, ’09 and ’10 — and B.C.’s Kelly Scott in 2006 and ’07 — combining to win the next six titles.

“Jennifer did it a different way than Colleen,” Bernard said. “Colleen was very calculated, and I would say risk-adverse.

“And then Jennifer was the exact opposite. She had aggressive strategy. She’ll walk out on the ice in the first end and throw a centre guard. Most teams, they don’t want to get into that until the second or third end when they get comfortable. She is comfortable from the first rock.”

Five rings are better than one: The Olympic era

The years: 1998-present

The rock stars: A dozen-plus Olympic medal-winning teams from Canada

Olympic curling dated back to a one-shot deal at the 1924 Chamonix Winter Games in France, followed by a demonstration sport at the 1932 Lake Placid Olympiad, which was won by Manitoba’s William H. Burns.

Then came demos again in 1988 Calgary — when B.C.’s Linda Moore won gold and Lukowich earned bronze — and 1992 Albertville — when B.C.’s Julie Sutton claimed bronze — before officially becoming an Olympic event in 1998 Nagano.

“When it was a demonstration sport, that kind of tweaked with me,” said Bernard, herself an Olympic medallist. “But when Sandra Schmirler went on to win a gold in Nagano 1998, that was like, ‘Gosh … you can actually win an Olympic medal at curling?’ And it was such a big, big deal.”

Also in Japan, Ontario’s Mike Harris captured silver.

And it’s been a wave of medals for Canada since at the Olympics — gold for Brad Gushue in 2006 Turin, gold for Martin in 2010 Vancouver, gold for Jennifer Jones in 2014 Sochi, gold for Brad Jacobs in 2014 Sochi, gold for Kaitlyn Lawes and John Morris in 2018 Pyeongchang, silver for Martin in 2002 Salt Lake City, silver for Bernard in 2010 Vancouver, bronze for Gushue in 2022 Beijing, bronze for Law in 2002 Salt Lake City and bronze for Shannon Kleibrink in 2006 Turin.

“Once the Olympics came in, people started popping their heads out of the sand to look around and go, ‘Whoa … there’s other teams doing stuff!’” Webster said. “And then the reality was that across the world, countries were like, ‘Oh, we want that Olympic medal.’ So that pushed the nucleus of Canadian curlers to be athletic and a little bit more sound.

“We had people come in that wanted to treat curling like it was a sport.”

Let’s get physical: The fitness era

The years: 2000s-present

The rock stars: Cheryl Bernard, Kevin Martin

The pursuit for Olympic gold lit the flame to get more fit.

Nobody did that better than the Alberta teams skipped by Martin and Bernard. They committed themselves to every detail of the game — not just the shot-making.

“We adopted more training, and we adopted fitness — and so did Kevin Martin’s team,” declared Bernard. “Both our teams at the Olympics kind of showcased fitness and how that can support brushing and shot-making.

“We were on the cusp of being full-time curlers. We all had jobs. There wasn’t enough money in curling until later on. But I would say at that point, we were trying to be full-time curlers and taking chunks of time off from work and training in the gym and that.”

Getting the mind fit also worked its way into the brains of those chasing excellence.

“Probably, maybe even the late ’90s is when people started to look at sports psychology books more,” Bernard said. “People were looking for an edge now, because curling was growing.

“It was, ‘Will fitness get us one more win at an event? Will sports psychology and the mental training get us two more wins in a year?’ Everybody was looking for that edge. Because you’re starting to see Olympics on the horizon, and you put in a lot more time and effort when there’s Olympics or Canadian championships out there to play in.”

Come together: The super-team era

The years: 2000s-present

The rock stars: The Howards, Brad Gushue, Kevin Martin, Kerri Einarson, Rachel Homan

Gushue’s push for Olympic glory led him down a path few skips before him dared take on.

That was to slot in another skip to round out his team — that being Russ Howard — in the Newfoundland and Labrador rink’s run to gold in 2006 Turin.

“I think Brad Gushue inadvertently created his own super team,” said Webster, of Gushue, third Mark Nichols, second Howard, lead Jamie Korab and fifth Mike Adam. “So you have one of the best skips in the world in Howard decide he’s going to play second. If that doesn’t give you confidence for Gushue being the youngest skip at the Olympics, I don’t know what does.

“And that worked out really well for Brad.”

It worked out pretty well again for Gushue and his super rink of Nichols, second Brett Gallant, lead Geoff Walker and fifth Marc Kennedy — for bronze — in the 2022 Beijing Games to go with a Brier win that same year.

In between time and in the face of curling traditionalism, super teams appeared all over Canada’s curling landscape.

Howard himself created arguably the first way back in 1989 by adding fresh-out-of-juniors skip Wayne Middaugh and his third, Peter Corner, to a lineup with him and his brother.

“It was acknowledgement that they wanted to go out and win,” Webster said. “It worked really well, because they all had great talent.”

Enough for Brier and world titles in 1993.

“And then Glenn Howard stole that strategy when he grabbed Brent Laing and Craig Savill out of juniors,” continued Webster of the Howard-Richard Hart-Laing-Savill Brier and world-winning lineup of 2007. “And then Martin was looking at how the game is changing and wanting to go young and athletic, and he didn’t care where they were from.”

That was the Alberta crew of Martin, John Morris, Kennedy and Ben Hebert — the 2008 and ’09 Brier winners and 2010 Olympic gold medallists.

“So Morris, who we assumed was going to skip himself to multiple Brier wins, is now a third,” Webster said. “It was like he was saying, ‘For me to have the best chance of winning, I’m going to play third.’ And you had Ben who stood out on the sweeping side of it.

“You didn’t have too many super teams on the women’s side until the last couple of Olympic cycles, and Einarson’s is the easiest one to acknowledge. You had four skips coming together (in Einarson, Val Sweeting, Shannon Birchard and Briane Meilleur).”

Of course, that Manitoba super team won four straight Scotties from 2020-23.

“And Rachel Homan asks Tracy Fleury to join her,” added Webster. “So Emma Miskew decides she’s going to play second and Sarah Wilkes switches to lead, and they win last year’s Scotties in Calgary.”

More freedom! The five-rock era

The years: 2011-23

The rock stars: The fans

The more free guards the merrier was needed to make curling even more of a party.

So the five-rock rule came into play — first at Pinty’s Grand Slam of Curling’s Canadian Open in December 2011, then in all the majors and in Curling Canada starting with the 2018-19 season.

That meant no rocks could be removed from the area between the hog-line and the house until before the sixth stone of each end is delivered.

“I would love to see guys like Russ Howard and Eddie Werenich play with the five-rock rule, because what was frustrating back in their days is even if you were only up one with hammer going into the sixth or seventh, there’s still a good chance you’re winning the game,” Webster said. “The analytics said if the ice doesn’t melt in the next four ends, you’ve got a 92 per-cent chance of winning the game. And the reality was the only way the other team got a sniff at it is if somebody bonked a peel.”

The evolving free-guard zone has helped to increase offence and — without a doubt — attract viewers.

“When you ramp up the degree of difficulty with the talent that’s out there now and they’re still making those shots, we have something we can sell on TV now,” added Webster.

The golden age of TV: The broadcast era

The years: 2000s-present

The rock stars: The fans

Television has long been a part of growing the game.

That can’t be ignored.

But — with all the eras we’ve recounted — curling’s become an ever-more can’t-miss sport on the flat screen.

“TV is massive,” Webster said. “And I think the best thing curling ever did — and still no other sports have ever figured out — is to mic up our players. You get to hear what the players are talking about. You get the inside stuff, and you’re listening to the emotion.

“If I’m watching the final of the Stanley Cup, the emotion I get to hear is from the announcers. I don’t get to hear Sidney Crosby on the bench going, ‘Holy, we need to do better.’ Imagine if you were able to hear it all the time. That’s what curling does all the time.”

The here and now: The elite era

The years: 2010-present

The rock stars: Kevin Koe, Brad Gushue, Rachel Homan, Kerri Einarson

What’s been brought to life on our screens and at the arenas is amazing sport.

They may have taken their cue from those before them, but make no mistake, today’s players are elite athletes.

Kevin Koe — the Brier winner in 2010, ’14, ’16 and ’19 — is considered by many to be the game’s top shot-maker, while Gushue — winner of the last three men’s crowns — is undeniably Canada’s kingpin.

There’s Jacobs — the 2014 Brier champ — Brendan Bottcher — the 2021 national king-turned-Gushue second — and Grand Slam winners Mike McEwen, John Epping and Matt Dunstone.

“By the time she’s done competing, Rachel Homan may very well be the greatest of all time and take that title away from Jennifer Jones,” Bernard said. “Rachel’s got so many years left, and she’s already so dominant. And they took fitness to a new level. She’s a transition to the younger, fitter professional teams.

“And Kerri? Her rise came from her edge of taking four skips and putting them together to build a team. I don’t think anybody thought it was going to work, and … wow … has it ever worked!”

To boot, they’ve become icons — easily accessible ones — for future generations of curlers.

“Gone are the days of my parents are curling, so I’m curling,” added Bernard. “Now you’re getting young curlers because they saw Kerri or Rachel or Jennifer, saying, ‘Oh … wow … I want do this!’

“And people can actually follow them these days on social media.”

The no-tick era

The years: 2023-present

The rock stars: The fans … again

Webster calls it the 5.5-rock rule.

Whatever your name for it, the no-tick rule is a further evolution of the free-guard zone.

“The rules had to keep up with the teams and the talent that they bring,” Bernard said. “With the five-rock rule and the no-tick rule, it’s about the rules keeping up with the talent of the players.

“Otherwise, it would be really boring if it was just a hit-and-peel game.”

Indeed, it didn’t take long for players to adapt to the five-rock rule and start moving around guards put up early in ends by just ‘ticking’ them into strategically better spots on the ice.

“Lisa Weagle got too good,” said Bernard, of the superstar lead who is 2017 world champ and three-time Scotties queen. “Everybody adopted the ability to tick the guard off the centre line, and the high-level curlers were all making it. High-performance curlers can make that tick-shot something like 93 per cent of the time, so then right away, the end is over because there’s no guards. The rule was put in for television and to build and grow the sport.”

And how.

“The three-rock rule was a really important start, but teams could hit so well that you needed to have more guards if you’re behind,” added Webster. “Four didn’t really make any sense, because you’re only benefitting the team with hammer, so five makes a lot more sense.

“And the no-tick rule is something that should’ve been brought in five, six, seven — maybe even 10 — years ago. But now it’s here, which is very important.”

What does the future hold? The next era

The years: 2025 and onward

The rock stars: Stay tuned

No … don’t expect curling’s evolution to dig in.

What else is next?

Well … Broomgate 2.0 is sure making things interesting right now, with it being part and parcel of the idea that every decade has somebody trying to find an advantage.

Shoe sliders, over the years, have advanced from thin teflon to thick teflon to metal.

Off the ice, the push will continue for more financial help from the Canadian government to try and keep our game on top of the world scene.

“Most — not all — of the international teams are funded by their governments,” Webster said. “Some are even considered government employees. So that’s their job and they practice four or five hours a day and they’re in the gym two hours a day. So that’s an eight-hour day every day.”

In Canada, Gushue, Jacobs, Homan, Lawes and Einarson are those full-time athletes trying to keep the nation an international force.

“Canadian teams aren’t funded to the same extent — they have full and part time jobs. The math just doesn’t add up. So the only way you can do it is sponsorship, and that’s hard. That’s where there’s a bit of a problem for Canadians. How in the heck do you keep up?

“But we have to find a way.”

“It is unbelievable the difference these days,” added Webster, about the entirety of the sport. “Just go watch Kevin Martin go beat someone in 1997 or 1998, and you’ll see the difference. And it’s not the talent level that’s different.

“Oh my … it’s a completely different game.”

One we love so very much.

tsaelhof@postmedia.com

On X: @ToddSaelhofPM

Postmedia is committed to maintaining a lively but civil forum for discussion. Please keep comments relevant and respectful. Comments may take up to an hour to appear on the site. You will receive an email if there is a reply to your comment, an update to a thread you follow or if a user you follow comments. Visit our Community Guidelines for more information.