Frequent pot use may be linked to psychosis in young people: Study

London, Ont., researchers have uncovered a potential link between frequent cannabis use and psychosis in young people.

Article content

London researchers have uncovered a potential link between frequent cannabis use and psychosis in young people, revealing connections between the drug and brain changes implicated in the serious mental health condition.

The new study by researchers at the London Health Sciences Centre Research Institute, the medical research arm of the London hospital, and Western University’s Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry analyzed brain scans of 61 patients to identify how cannabis use is linked to biological changes in the brain associated with psychosis.

Recommended Videos

“What we have seen over the last several years, especially since cannabis legalization in Canada, is an accelerated presentation of first-episode psychosis among young people,” said Julie Richard, psychiatrist and physician lead at LHSC’s Prevention and Early Intervention Program for Psychoses (PEPP) program.

“We’re now regularly seeing teenagers who are experiencing transient or sometimes more prolonged psychosis after exposure to cannabis products.”

The London research team studied participants aged 18 to 35 years old. The team studied one group of patients who did not use marijuana and another with people who used cannabis regularly over an extended time period.

Some study participants in each group were also diagnosed with first-episode schizophrenia through PEPP.

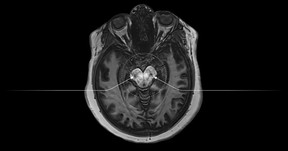

The researchers used brain scans to track neuromelanin, a substance that accumulates over time if there is too much dopamine, an important chemical messenger in the brain that helps process motivation, mood and motor control.

Some dopamine is normal and necessary, said study author Jessica Ahrens, but too much can interfere with typical brain processes and may increase the risk of psychosis, particularly in individuals who are already vulnerable or young people whose brains are still developing.

Neuromelanin, which is a breakdown of dopamine, appears as black spots on the scans, helping scientists measure and identify areas with high dopamine activity.

The neuromelanin spots in the brains of people who reported excess cannabis use were darker than they should have been for their age compared to healthy individuals, the researchers found.

In some cases, the people with cannabis use disorder had pigmentation in their brains that someone 10 years older would be expected to have.

“Everyone has dopamine, and everyone has neuromelanin too. It does increase as we age,” Ahrens said. “We’re looking at an increase in this group who uses cannabis regularly. It’s increasing at a rate that it shouldn’t be.”

But it is not just the presence of the neuromelanin that has the London researchers concerned. Where the pigment was showing up in the brain was significant too.

The black spots were seen in a midbrain location associated with psychosis, the study said. This was true of the study participants with cannabis use disorder, whether they’d had a psychosis episode or not.

“Our study shows it is quite possible that people who have been smoking weed for a long period of time have an increase of dopamine in the same area of the brain that would lead to psychotic symptoms,” said Lena Palaniyappan, adjunct professor at Schulich and the senior author of the study.

“This research is exciting for us because it allows us to show young people where the damage is happening. . . . Until now we haven’t had any physical proof correlating mental health struggles to cannabis,” added Richard.

The availability, and potency, of cannabis products post-legalization may be a factor in what PEPP has been seeing in recent years, Richard said.

“We regularly hear of adolescents that were using cannabis by 12 or 13 and are using regularly by 15 or 16 years old,” she said. “There are brain effects that are happening and we’re really just catching up to the science of it.”

Psychosis is a mental health disorder that can cause people to hallucinate, hear voices, lose their motivation or withdraw from social activities.

“It’s not only something that affects the individual. It affects families and social networks,” Palaniyappan said Wednesday. “When it happens at an early, formative stage in our lives, 18 to 20 years old, that’s when people are in school, trying to work. All of that is toppled by having a severe psychotic episode.”

The research team wants to build on its most recent research by seeing if interventions to help young adults reduce or limit marijuana use can slow the process the London researchers observed on the brain scans, Palaniyappan said.

The London research study was published Wednesday in JAMA Psychiatry, an American Medical Association publication.

Postmedia is committed to maintaining a lively but civil forum for discussion. Please keep comments relevant and respectful. Comments may take up to an hour to appear on the site. You will receive an email if there is a reply to your comment, an update to a thread you follow or if a user you follow comments. Visit our Community Guidelines for more information.