DE LUCA-BARATTA: Canada’s other supply management problem

Article content

While Canada-U.S. trade negotiations reignite debates over supply management for dairy and poultry, Canadians overlook a far costlier system — the unofficial supply management of housing through restrictive land-use regulations.

Most Canadians support weakening or abolishing the current agricultural supply management program, a long overdue realization. Under this program, a national marketing agency sets provincial production quotas for eggs, poultry, and dairy. Farmers then receive permission to produce and sell a set amount of each good at a guaranteed minimum price. A University of Manitoba study found that families pay over $900 million more per year for supply-managed goods than they would in a free market.

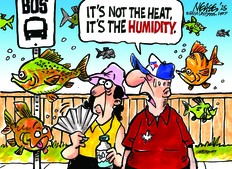

But the effects of Canada’s second, unofficial supply management system are much worse. Through a web of urban planning rules, municipalities prevent housing construction from keeping up with growing demand, causing home prices and rents to balloon.

The two systems differ in their details, but not in their effects, because the underlying economics are the same. When the government artificially constrains supply, consumers foot the bill through higher prices.

Under supply management, the federal government directly sets production ceilings to stabilize prices and guarantee farmers’ incomes. This system protects farmers at the expense of consumers, who pay more for groceries than they otherwise would.

Under land-use regulations, local governments limit building heights, set aesthetic standards, ban certain types of construction in designated areas, and impose other rules, such as parking requirements and minimum lot sizes. These rules have various goals, from environmental protection to the preservation of historic neighbourhoods. However, by making housing harder and more costly to build, they also constrain supply and radically inflate prices.

Individually, these rules may seem reasonable, but cumulatively, they stifle development by outright banning projects or layering costs that render new housing unprofitable. The result is a shortage of housing, most of which becomes too costly for the average homebuyer or renter.

When more people bid for goods, the price of those goods rises. In a free market, producers respond by producing more of them, lured by the prospect of higher profits. Over time, as more producers enter the market and existing firms compete with one another to attract buyers, prices decrease to attract new customers. Firms that overcharge lose revenue, since customers can simply move to a seller offering a better deal.

In Canada, construction of new housing has not kept up with demand for decades, because developers cannot respond to higher prices by simply building more units. When they do manage to build, the process is usually extremely costly. Those costs are ultimately passed on to homebuyers and renters. Excessive land-use regulations thus make luxury-tier housing the only kind of housing worth building.

A study by the C.D. Howe Institute found that in eight urban areas — Vancouver, Abbotsford, Victoria, Kelowna, Calgary, Toronto, and Ottawa-Gatineau — homebuyers paid an extra average of $230,000 for a new house due to land-use regulations that prevent new construction. In Vancouver — where the average home costs $2 million — regulatory costs account for nearly half the price. In Toronto ($1.2 million average), it’s 20%.

This system is especially unfair to young people, who often find themselves priced out of the housing market altogether. To understand just how unaffordable housing in Canada has become, consider a family earning $183,000 per year, nearly $100,000 above the median Canadian household income. That family would have to set aside 10% of its income for 15 to 25 years (depending on the income split between the spouses) to afford a down payment on a house in Toronto. The average young family simply does not stand a chance.

Those who blame greed instead of overregulation for Canada’s housing crisis should look at cities with few land-use regulations, like Houston, Texas. For the most part, builders are free to build in response to demand. The median home price in Houston is about $350,000.

Houston’s developers are no less “greedy” than Toronto’s; they’re simply constrained by competition in a freer market. A relatively free housing market incentivizes them to compete for customers through lower prices and an almost non-existent regulatory burden allows those prices to remain quite low indeed.

The same can be true in Canadian cities if governments get out of the way.

It’s about time for Canadians — young Canadians in particular — to start demanding that local officials get rid of regulations that price them out of the housing market. Federal and provincial governments must penalize those who cling to obstructionist rules.

Canadians are tired of overpaying for a carton of milk — and rightfully so. It is time we lost patience with paying too much for housing, too.

Anthony De Luca-Baratta is a contributor to the Center for North American Prosperity and Security, a project of the Macdonald-Laurier Institute

Postmedia is committed to maintaining a lively but civil forum for discussion. Please keep comments relevant and respectful. Comments may take up to an hour to appear on the site. You will receive an email if there is a reply to your comment, an update to a thread you follow or if a user you follow comments. Visit our Community Guidelines for more information.